July 15, 2020 | Blog

The Belief That Everyone has a Voice: The History of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

From Rain Man and Temple Grandin, to Atypical and The Good Doctor, Hollywood’s portrayal of a person with autism is often someone who communicates their wants and needs verbally. However, anyone with a familiarity with autism knows that there is an often-misunderstood population of autistic individuals who cannot communicate verbally or communicate effectively on their own.

For many years, it was assumed that if someone’s thoughts weren’t able to be spoken aloud, they had intellectual disabilities combined with their autism. The barriers to communication represented a person’s totality.

Now, thanks to the development of current Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) strategies and devices, such as the iPad and Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS), many people with autism can express their thoughts, needs, and wants independently.

This article will briefly summarize the origins of AAC strategies, systems and devices, beginning with one you may recognize–sign language. With origins in Ancient Greece, sign language has the distinction of being the oldest AAC system, with Morse Code, from the 19th century, being the second oldest.

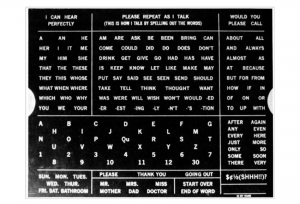

In 1920, the first actual known AAC device, the F. Hall Roe Communication Board, was created. Co-developed by F. Hall Roe, who was suffering from Cerebral Palsy, the Communication Board contains letters and words that a person can point to and construct words or sentences. The distribution of such a device was made possible by the Ghora Kahn Grotto Benevolent Society.

The first electric machine used extensively to speak was developed in the early 1960s by hospital volunteer Reg Maling. A predecessor to contemporary computer keyboards and tablets, this machine was known as the POSSUM (Patient Selector Operated Machine), or a sip-n-puff. The device works by inhaling or exhaling through a tube-shaped device to send signals, typewriter controller that controls aspects of the surrounding area. While it was for home-use only, it was still an advancement during a time when the Disability Rights Movement started making progress.

A decade later, the first portable AAC devices reached the marketplace. The “Talking Broach,” a keyboard with a display fit for a breast pocket, and Toby Churchill’s “Lightwriter,” which was like the “Talking Broach” but had a longer two-way display, went on the market. The 70s were also known as when Speech Generating Devices (Or SGDs) started to make significant strides with devices like the “Handivoice,” which had voice output, portability and used numerical codes to create words.

The next time we approach the subject of AAC strategies and systems, we will explore its more contemporary history and the myths associated with AAC.

Image Credit: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-F-Hall-Roes-communication-board-consisted-of-letters-and-words-printed-on-Masonite_fig8_6196605